The Podcast Pipeline

On The Critic and Her Publics and intellectuals at work in the content mills

I was laid up with pneumonia in February so only this month have I caught up with Merve Emre’s The Critic and Her Publics, a rather disheartening artefact of critical culture in the age of content mills. Each episode delivers insights about the career trajectories of critics, along with many satisfying aperçus, but what the series really demonstrates is the compromises required of public intellectuals when they seek to go big on digital platforms.

The Critic and Her Publics is a virtuosic exercise in digital strategy and content leverage. It provides a diligent and well-resourced answer to the question, how do you build an audience, a public, around literary criticism? There is a commonsense answer to this question: publish it. That’s the golden age of criticism theory. Good writing will find its readers. Maybe, insofar as every now and then great pieces do go viral, and a few publications that consistently publish good writing do have loyal, paying audiences. But virality does not equal sustainable revenue or audiences. Idealistic independent publications continue to publish critical writing that they think is important to the world, thank the gods, but few of them are able to pay their contributors very much. There seems to be a consensus, who knows whether it is well-founded, that a podcast is a more reliable means of capturing attention than a long critical essay. As she listens, a member of the podcast public can do the dishes, drive to work, jog round the park. A representative of the reading public might be able to load up her commute with an essay, but her ability to multi-task is limited by the medium.

The problem is, it’s much more expensive to produce a podcast than it is to commission and publish critical writing, especially online. More people need to be paid, and most of them, unlike writers, aren’t in the habit of accepting honorariums. This is why, if you were going to pour resources into developing a podcast devoted to criticism, you would need to take a rather clear-eyed approach to building and retaining a digital audience. What would a digital strategy wonk advise? Something like this, I think.

First, you need star power. Ask the equivalent of a celebrity critic to host the podcast. Readers of a range of publications should recognise the host by name. She must have an impressive academic pedigree and a professorship with a splendid title. You’ll want her to understand how social media works, to have fronted a million events and writers’ festival panels, to have been interviewed herself on every podcast going.

Bring in guests who already have media profiles. Don’t befuddle the audience with names they don’t recognise. Flatter them with familiarity. You will want to throw off any suggestion that this is a fusty exercise in gatekeeping. No old white dudes.

Make sure you have the backing of a big institution, like a university, though a major library or cultural museum might work too. Find an advertiser, such as a publisher, but call them a partner not a sponsor.

Reach is important, so set up partnerships with prestigious publications. You’ll want the content to appear on their platforms, to reach their networks. Tell them it will build their audiences and help them connect with new subscribers, or some shit like that.

A lot of podcasts that feature academics sound terrible. Audiences hate this. Figure out a proper budget for editing and mastering. Hire a sound engineer. Hire a designer and ask them to create a set of beautiful digital assets.

As for content, it should be stimulating but not so demanding that the listener will lose the thread if she’s at the gym or stuck in traffic. Chatty. No lectures. The episodes should not be too long.

You’ll definitely need a gimmick.

If you heeded this advice, you’d wind up with The Critic and Her Publics.

Each episode of the podcast is a recording of a live event, a conversation at Wesleyan University, where Emre is Shapiro-Silverberg University Professor of Creative Writing and Criticism and director of the Shapiro Writing Center.

Lightly edited transcripts of the conversations are published by the New York Review of Books on their website. (There’s something about the copy below that really rankles. An ‘extensive look’? I guess it’s better than the ubiquitous deep-dive.)

Transcripts of the conversations are repackaged and published under different titles at LitHub. Note the transition from ‘today’s sharpest working critics’ in NYRB to ‘brilliant minds at work’ in LitHub. Publishing transcripts makes podcasts accessible to readers who can’t or don’t want to listen, and it makes it easier for other writers – whether they’re writing a newsletter, researching a scholarly monograph, or skimming for a snitchy tweet – to quote the material. Transcripts are low-hanging fruit for digital publications because they don’t have to devote substantial resources to commissioning or editing them. LitHub’s publishing model relies heavily on such repackaged content, which also includes excerpts from new books, the NYRB’s not so much (although most of the guests on The Critic and Her Publics are also contributors to the NYRB). The hope is that this kind of content partnership will be win-win for the organisations involved. The podcast extends its reach, and has a bigger audience footprint to report to whoever is interested (funders) and the publication might see a little uptick in traffic, maybe even new subscribers. Whether readers or the culture at large benefit is another question, to which my answer would be a shrug of resignation.

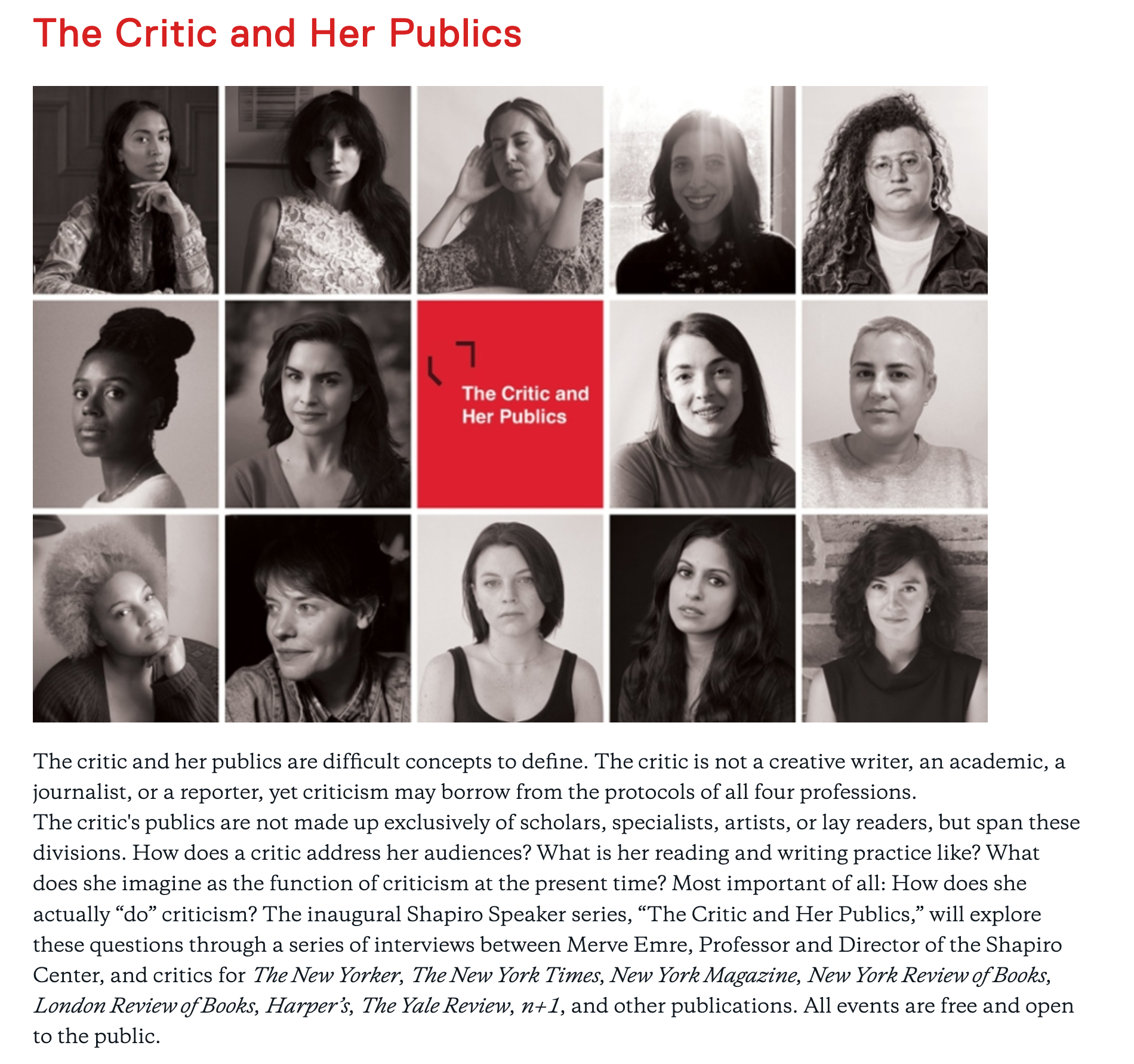

The podcast itself has a strong brand identity, organised around an illustration of Emre by Leanne Shapton and headshots of the interviewees. The digital assets are easy and appealing to share, not even a bit fusty. As the images signal, there’s nothing DIY here! There will be no interviews conducted via Zoom, no outros recorded in a makeshift closet-studio, and no one took their headshot with their phone.

So who are today’s sharpest working critics? Well, they are young to young-ish, based in the US, writing in English (or rather, writing for publics who read English), well-networked, and active on social media. There is a fairly narrow pool of publications to which they all contribute: the New York Review of Books, n+1, the New Yorker, Harpers’, the New York Times, New York magazine, Bookforum. You get the idea.

Oh, and they’re all women. It’s her publics, after all. One of the decisions that has been made about this podcast is to make it about gender – but also not about gender. No one is asked to reflect on the experience of being a woman critic, or a woman critic of colour, or to speak directly to identity in any way. This is something of a relief after years of often turgid rehearsals of the identity politics around criticism, of women critics being gathered to talk about their lived experience as women critics rather than about critical practice. It is a conspicuous choice, one that keeps a distance from the early 2010s battles over the representation of women in critical culture. It seems like a bit of a missed opportunity to gather writers of this calibre and then not to ask any questions at all about gender, but the format is so constrained that much is left by the wayside.

The first half of each episode is a kind of career advice session, in which Emre speaks for about twenty minutes with her guests about their professional trajectory. She asks them to tailor their answers to the Wesleyan undergraduates in the room, many of whom are studying criticism with Emre herself. How did Andrea Long Chu wind up as resident critic at New York mag, able to devote months to reading and thinking before filing killer pieces? How do you get a gig as a New Yorker staff writer? What is the source of Anahid Nersessian’s productivity? Each interviewee offers very good-natured and distinctive responses to Emre’s questions. The problem is, the interviews are over before they begin and they yield no surprises about literary careers in America here: start with talent and drive; go to a prestigious school, move to New York, work your connections to the literary and media worlds; get a break and make the most of it.

After the ad break (thanks Knopf!), Emre presents her guest with a text and invites a spontaneous critical response. The live audience has a copy of the text stuck under their chairs so they can read along and contemplate how they might fashion an impromptu response of their own. It’s an exercise inspired by I.A. Richards’ Practical Criticism and one that Emre uses in her classes at Wesleyan. Indeed we are told that Emre’s students selected the poem presented to Nersessian to interpret. In spite of this intellectual and pedagogical pedigree, in the podcast environment, it’s a gimmick, a hook to keep the listener’s attention for another twenty minutes. Will the critic recognise the text? Will she place it in the correct century? Will she be able to say something about it on the spot or will she embarrass herself? I described The Critic and Her Publics as disheartening above, and that’s because Emre brings together this stellar group of public intellectuals, establishes their diligence and their discipline – and then asks them to participate in the podcast equivalent of a reality TV stunt.

This performance is designed to reveal the critic at work. Emre prompts her guests to demonstrate how they’d approach the text, how they’d begin to fashion a reading. Instead of demystifying the process, or democratising criticism, per Richards, this second section of the podcast pivots to farce, presenting a debased version of public intellectualism. Hannah Goldfield is asked, in an excruciating sequence, to sample cookies baked by Emre and her students, and to deliver feedback on each one. Nersessian gives a frenetic performance of close reading and is very entertaining as she picks up words and phrases for examination. I struggled, though, to see this as anything but a weak substitute for a developed critical reading. The hours I passed listening to The Critic and Her Publics would have been better spent reading essays by Merve Emre and her interviewees, no doubt about it.

The Critic and Her Publics is unsatisfying not because any of the brilliant people involved are doing a bad job. They’re all doing exactly what’s required of them in this format. Excellent digital strategy, it seems, asks for polite japery in the name of engagement. I note too that the register of every episode is extremely courteous. Everyone is happy to be there, to be contained by the format. It’s all just content and in the end it sounds like every other podcast.

Anyway, who are all these publics? Is The Critic and Her Publics a brand-building tool for the Shapiro Center, a twinkle in the eye of an administrator seeking to boost recruitments? Is it grist for the LitHub content mill or a hook for potential subscribers to the New York Review of Books? I admire these writers greatly and seek out their work, as I do Emre’s. It’s no insult to anyone involved to observe that appearances on public platforms such as The Critic and Her Publics are exactly the kind of brand-building work that agents urge their writers to perform, that university department heads and Vice-Presidents of Engagement like to see academics undertake. It’s hard to escape the suspicion that these publics are all actually somebody’s market.

I am still attached to the idea that literature and critical culture can be forms of resistance to the transformation of the public sphere into a giant mall, a place where everyone has something to sell, everyone is in on the hustle. Not in this instance. The Critic and Her Publics is a gloomy reminder that once you step into the content mills, the only thing that gets churned out is content.

An obvious counterpoint to The Critic and Her Publics is The American Vandal, produced by Matt Seybold at the Center for Mark Twain Studies at Elmira College, particularly the recent series Criticism Ltd. asks a great deal of listeners. The episodes are long and often pretty baggy but they absolutely fizz with ideas and energy. Merve Emre has been a guest on The American Vandal, on a terrific episode on autotheory and autofiction with Anna Kornbluh. Seybold lets his interviewees go on and on, lets them figure out their own register. It can take a while for a given episode to get to the point. As I’ve been told by several twitchy academics who own excellent headphones and have become adept at recording their lectures on Zoom, the production values are shaky. All true, but I like the shakiness, as it signals a certain openness to risk. Maybe I’m just betraying my love of lo-fi sounds and DIY production. The scripts need to untangle interviews in which academics interrupt each other, repeat themselves and circle around their arguments. You can hear Seybold trying to figure out an audio structure that will carry these complex conversations, scripting segues and transitions, editing like a fiend to organise the material. It’s easy to lose track if you’re not paying attention – but that’s the point, it’s worth paying attention.

Content partnerships can take you to strange places. You start by making a podcast, who knows, you might wind up as a cruise leader. Has the Cruise Essay genre been exhausted? You will not find out the answer to that question if you hop aboard the Australian Literature Festival at Sea 2024:

Find yourself captivated by award-winning authors and fellow readers on the inaugural 5-night Australian Literature Voyage at Sea, curated in partnership with Australia’s oldest bookstore, Dymocks.

Land ho!

Thanks for reading Infra Dig! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.