Big thanks to my creative muse

Does it really matter if an author uses ChatGPT to help them write their book?

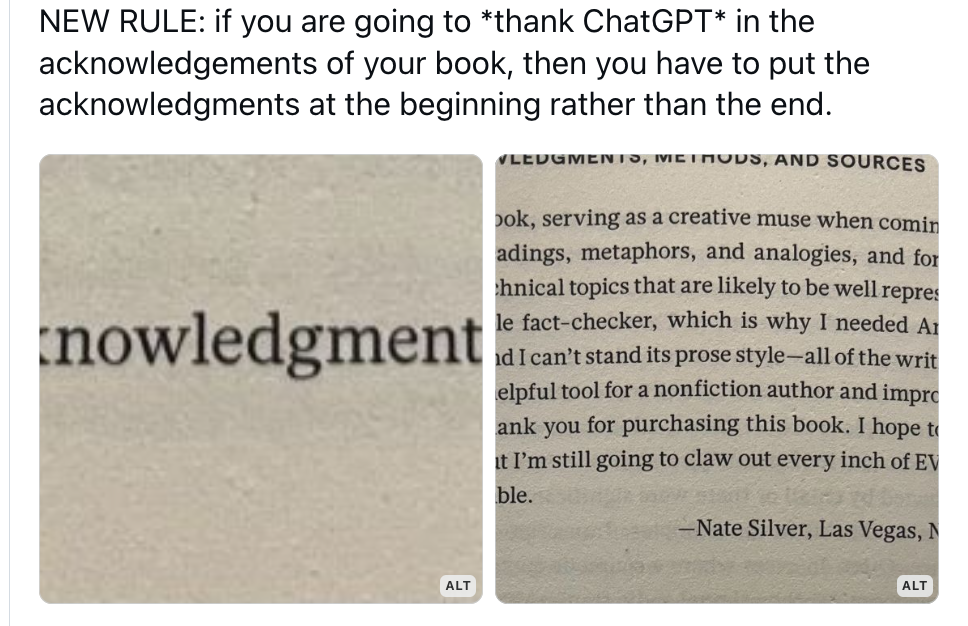

Last month, a shot of the acknowledgements from Nate Silver’s On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything did the rounds. I saw it here on Bluesky, buried in a very long takedown thread, which starts, ‘JFC Nate Silver’s new book is over 450 pages. Was the advance not big enough to afford an editor?!?’, and goes on for about a million posts. If you’ve bemoaned the ascendence of poll-driven electoral analysis and forecasts in contemporary media, you’ve got a beef with Nate Silver. It seems that many statisticians and risk analysts, a cohort among whom I do not count myself, also have methodological differences with Silver.

Silver started the FiveThirtyEight site during the 2008 election and is an apostle for the use of statistical methods to make sense of current events, and, well, everything. Here he is in the Guardian giving good soundbite as he promotes his new book, which is, I gather, a disquisition the art and science of calculated risk that invites his readers to spend a great deal of time in casinos. Silver left a career of professional punditry to live the life of a professional poker player. On the Edge follows his 2012 bestseller, The Signal and the Noise (notable for a humdinger of a subtitle, ‘Why so many predictions fail – but some don’t’, aka a bet each way). I’m not particularly interested in the content of On the Edge, to be honest, or in Silver himself, though it’s relevant that he remains resistant to the truth claims made via non-numerical methods. But I am interested in is his acknowledgement of ChatGPT as a writing tool.

Here’s the post:

And here is the text buried in those images:

One more newfangled acknowledgement: ChatGPT was a significant help in writing this book, serving as a creative muse when coming up with things like chapter subheadings, metaphors, and analogies, and for refining my understanding of technical topics that are likely to be well-represented in its corpus. It is not a reliable fact-checker, which is why I needed Andy and the Penguin Press team. And I can’t stand its prose style – all of the writing is my own. Nonetheless, it’s a helpful tool for a nonfiction author and improved my productivity.

Of course the quant guy used ChatGPT to help him write his book! Although I read this acknowledgement as first and foremost an effort to troll the earnest reader, anybody who dubs ChatGPT their creative muse warrants disdain. The anti-Silver legions on Bluesky went to town on these acknowledgements, and who would deny them their sport?

‘All of the writing is my own’, says Silver – except for the metaphors and analogies, some of which come from his thirsty muse. From what I’ve gleaned from interviews with Silver, the book’s central conceit is a division of the world into denizens of the River (risk-takers) and of the Village (cautious stooges), so metaphors are not exactly unimportant to the broad project. To claim your writing as your own but to credit ChatGPT with your use of figurative language suggests that you don’t believe that figurative language means all that much, that form is subordinate to content.

And what does it mean to use generative AI to refine your understanding of technical topics? I imagine this means asking the bot to generate a set of context-relevant crib notes which are then rewritten and integrated into a bigger text. (I need crib notes on the Bayesian principles that Silver uses like a rhetorical shield, as they seem to be the flashpoint for the methodological objections raised to his work by other statisticians. Who’s right? No idea. Anyway.) ChatGPT can also provide answers to more sophisticated prompts than Google search can, and I suppose would be helpful for laying down pathways into specialised bodies of knowledge. To conclude that ChatGPT wrote Silver’s book for him is to wilfully misread the acknowledgements – but it is hard not to see also a degradation of both writing and research in this brief text.

Still, even though my intuition bellows that it’s wrong, it’s all wrong, I am tempted to make a contrarian argument that it doesn’t really matter all that much that Nate Silver used ChatGPT to help him write his book. That’s in part because Silver’s book, and other big boring bestseller prestige non-fiction marketed to lay readers wanting to come off as experts, business books and popular science in particular, are solid empirical examples of corporate authorship, which may not be quite the same as collaborative authorship, but certainly involves more than one person. The idea that but for ChatGPT, the reader of On the Edge would have encountered Silver uncut, is a nonsense. With or without Silver’s creative muse on deck, a cohort of human specialists would have had their hands on that manuscript prior to publication to make sure the book sounded the way a Nate Silver book should sound: agents, editors, fact-checkers, sales and marketing execs. They would have tuned his metaphors and subheadings for him had ChatGPT not been there to do so. This is risk management for publishers. Big ticket non-fiction, even in the relatively small Australian industry, involves researchers who sometimes sub in as ghostwriters, and a lot of editorial slog work so that the published book is calibrated to meet reader expectations. (Just ask… that guy whose market is people who don’t know what to buy their weird male relative with an interest in military history in the family Kris Kringle. Has he got a new one out this year?) Essentially those publishing workers are tasked with ensuring that the book sounds like what readers want Nate Silver to sound like.

The books that matter to me don’t resemble On the Edge at all, including, I speculate, during the pre-publication editorial process. I would be surprised and probably – maybe? – distressed if I found out that the books that I am currently reading, by Rachel Kushner and Emily Witt, were co-authored by ChatGPT. One of the threads of Christian Lorentzen’s recent Granta critique of Dan Sinykin’s theory of conglomerate authorship, is that Sinykin overstates the shaping influence of publishers on works of literature, as distinct from commodity-books like On the Edge, that publishers are essentially part of the reception of literary works, rather than involved in the production of their literariness, that manuscripts by Kushner and Witt have been more or less authored by the time they land on the editor’s desk.

On second thoughts, perhaps I wouldn’t exactly be distressed if the next book by Emily Witt included a nod to ChatGPT in the preface. I’d be surprised, and I’d be curious. But that is because reading the work of authors over a long period does involve a set of projections and fantasies about authorship, about the identity of the author. I’d assume that an intelligent process-driven author like Witt (see there, the projection of Witt as a certain kind of author, the projection of myself as a reader invested in a certain kind of writer) was experimenting with ChatGPT, and that she would observe and report on that experimentation, and in doing so challenge the sentimental myths of authorship, including the big one, which is also a necessary legal fiction, that every word we read in a printed book is a direct emanation from the mind of the author.

A more plausible scenario would be a Sheila Heti novel with an acknowledgement of ChatGPT tucked somewhere into the paratext. Heti has used coins as a generative writing technology (in Motherhood) and her most recent book, Alphabetical Diaries, had its roots in a spreadsheet of alphabeticised sentences from her diaries. In 2022 a five-part conversation between Heti and a chat bot named Eliza was published by the Paris Review. (Heti’s first question: ‘Hi Eliza. I am wondering whether the internet is literally hell.’) For Heti, authorship is editing, selection, combination, not a fantasy of unmediated self-projection (cf the Joycean ‘Arranger’); it’s always a delight to think with Heti about the limits of authorship, about the relationships between authors, their lives and their texts.

If there is a sinister note in Silver’s acknowledgement, it concerns productivity. ChatGPT ‘improved my productivity’, he writes. Now we’re squarely back in the arena of corporate writing and publishing. Non-fiction writers in particular are under immense pressure to be efficient, and to write their books to a deadline determined more by current events and perceptions of market demand than by the demands of the subject matter. No doubt it is quicker to ask ChatGPT to slog through technical material and produce summaries than it is for an author to undertake the work themself, and to form an understanding of those topics in context – but the cost is obviously the depth of engagement, and the capacity to query or contest existing bodies of ideas. On the Edge will probably be a bestseller – this kind of prestige Big Ideas non-fiction attached to a high-profile writer is a zero-risk proposition for publishers – and Silver’s embrace of ChatGPT may serve to normalise its use by other writers, or even to create an expectation that it is used to speed things up. Will it make it harder for writers to argue that they need time to research their books, as well as to write them? Possibly.

As I was thinking about this question – what does it matter to readers if an author uses ChatGPT to write their book? – I read this brief conversation about art and AI between two old internet heads and editors, Tom Scocca and Maria Bustillos, first published on Flaming Hydra (parenthetical digression: Flaming Hydra publishes great writing online, especially on digital culture, runs as a kind of collective). I’m easily inclined to treat questions of authorship as abstract, to zone out in the spaces opened up by poststructuralism and experimental practice, and to do a paint-by-numbers death of the author. But to do so risks discounting the human connections forged through reading books authored by real people, and undermining reading as fundamentally a social practice.

Here’s Bustillos:

I would rather read BAD fiction written by a real person than “good” anything made by an AI, is what I want to say. But even if it could fool me into thinking a real, and bad, writer wrote something, I wouldn’t feel caught out, I would feel I’d been swindled, by a disgraceful person. The machine doesn't try to fool you by itself; a person tries to fool you.

I appreciate the way this conversation dislodges quality of writing as a moral basis for assessing AI, as if ‘good’ AI writing were any more acceptable than ‘bad’ AI writing, at least in terms of copyright and the devaluation of creative labour. It’s less of an aesthetic question, then, than an ethical one. They also set up a good faith reading compact between reader and authors that sounds a little twee in the echo chamber of post-structuralist theory, but also reflects the kind of trust readers implicitly place in authors and publishing processes. There’s an echo of this argument in the conclusion to Andrea Long Chu’s long piece on Sally Rooney in NY Mag this week:

the reader who searches for the author within or behind the work is also doing precisely what the characters in a Sally Rooney novel learn to do: She is refusing to see the novel as an abstract quantity. She is insisting that it is a relationship between people.

(I haven’t read many of the reviews, let alone the novel itself, but there’s enough Intermezzo discourse currently in circulation to power a small rocket, so I won’t add to the heap.) I suppose in acknowledging his use of ChatGPT Silver is striving to keep that compact with his readers, especially with his insistence that ‘all of the writing is my own’. He’s not trying to fool anyone, but also, he’s perhaps less available to readers as the author or the mind within the work.

What, finally, does all this mean for critics? Does the slow drip of generative AI into publishing create new expectations for critics, in particular, to police the use of ChatGPT as a writing tool? As generative writing tools improve, it’s not fanciful to suppose that more writers will use ChatGPT to get to deadline. If publishers don’t pick this up and discuss it prior to publication, should critics be expected to? I’ve always been of the view that critics should prioritise reading the book in front of them, rather than building their readings around projections of authors and how they work. The author shouldn’t matter too much, even though they always do. Reviewing memoir and autofiction immediately and obviously complicates this easy high-mindedness, as anyone who’s tried to do so knows.

In spite of the fact that readers (and editors) tend to expect critics to be able to detect plagiarism and outright fabrication, often critics are unable to do so. Australian literary history provides abundant examples of literary critics failing to pick up plagiarism, fabrication, and other forms of ethical malfeasance, most recently in the case of John Hughes, and most notoriously in the case of Helen Darville. We, and by the plural I suppose I mean, we literary critics, flatter ourselves if we are certain that we will be able to recognise word salads and hallucinations as generated by ChatGPT rather than an author. Furthermore, right now, it’s rare to see analyses of literary value – this is bad writing – that are couched in style and aesthetics rather than in politics and ethics.

It’s probably ethical that Silver did declare his use of ChatGPT. He can’t be the only big name non-fiction writer on a deadline to have used these tools, and he won’t be the last. In the unlikely event that I were asked to review Silver’s book (and, haha, said yes to the commission), what would I do with his acknowledgement of ChatGPT? Use it to berate him for his lack of originality? That would seem like a daft kneejerk reaction. More likely I’d seek to correlate inconsistencies and incongruities in the work to the use of generative AI. I’d scrutinise the subheadings and analogies, and the technical summaries, looking for holes. In other words, with the fantasy that a person had sat down and written the book under their own steam shattered, I’d be distracted from the work at hand.

My thinking about all this remains woolly, but I’m not yet convinced that readers should have to rely on critics to figure out whether a book has been written with the aid of generative AI. During the Hughes affair some academics professed themselves incredulous that literary critics didn’t pick up on plagiarism that would have surfaced in a jiffy through the use of software such as Turnitin. This seems to me to transform the role of the lay critic into a kind of glorified factchecker who must verify through empirical means the originality of a work – and suggests a complete loss of trust in both publishers and writers, a hermeneutics of extreme suspicion. If the responsibility to detect use of chatbots lies anywhere, I think it must lie with publishers, and be part of their conversations with writers about the development of their work, about references and attributions. At this stage in the history of generative writing technologies, a disclosure about use of ChatGPT doesn’t sound ridiculous, but I have a feeling that in five years, acknowledging ChatGPT will sound about as silly as acknowledging use of Google or Wikipedia.

I’m very curious as to what other writers, readers, editors and critics make of all this - does it matter if a writer uses ChatGPT to help them write their book, and if so, why? Should critics be tasked with sniffing it out?

A few good things to read:

‘The writers asked themselves: What was of the now? Their output illustrated the uncertainty. Was Beyoncé the thing? Or was it “the golden age of television”? Was it the decision to have children in the age of climate change? Was it a true-crime podcast? Was it the alienation of contemporary exercise regimes? Was it articulating generally observable social media trends? A person could try to fit into an established mold, and be, say, a hard-boiled war correspondent, but even our country’s unlawful massacres abroad no longer had the power to compel the public. The writing was laden with hyperbole and false epiphany. It anxiously attempted to convince the reader of the importance of unimportant things – the genius of our mediocre pop stars, of the revolutionary nature of token political symbols. Very little that was written pierced the ersatz nature of the world around us.’ – Emily Witt, Health and Safety. Terrific book, and if I were going to review this one (anyone?), I’d start by thinking about how it imagines the horizons of women in their thirties and forties, and argue that it’s a radical and intelligent alternative to all the divorce/perimenopause/midlife books that have been published this year. Read this instead of All Fours and Liars, please. That said, I have reached my absolute limit with high-minded accounts of long nights at Berghain. Seriously, enough!

‘I could write something called “Not Writing.” I am writing it. Soon, I’ll have been the one who wrote it.’ – Not Writing by Danielle Dutton in n+1.

‘The conversations surrounding the humanities in liberal-leaning mainstream publications are of such carelessness and scandalous frivolity that you begin to understand why we are so readily erased by dumbfounding clichés and stereotypes.’ – ‘The Humanities are Worth Fighting For’ by Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado in the LARB.

The SRB has a beauteous new website (which also makes it much easier to browse the journal’s capacious archive)!

One absolute stinker:

Two former fiction editors of the Crab Creek Journal reflect on getting fired after a story they loved got canned by their EiC.

I’m putting this link at the end of the newsletter because it’s such a reactionary piece of crap and I don’t think it deserves the traffic. Honestly, had it not been published by a magazine whose stock in trade is reactionary pieces of crap, I’d believe it was written by AI, so dutifully does it accumulate the tropes and clichés of anti-wokism. It’s time to say adieu if you are not interested in the following topics:

- literary journals and their processes

- bogus definitions of censorship

- idiotic libertarian defences of racist writing

To save you the bother of reading, a précis: the fiction editors happened upon a short story they loved in the slush pile, which was a re-interpretation of the Lone Ranger, a re-interpretation that centred the relationship between the Lone Ranger and his Native American sidekick Tonto. A generous reading of the story is that it’s about the Lone Ranger’s discovery of his sidekick’s humanity. In the story, Tonto speaks a kind of pidgin English and is basically presented as a child. My reading of the story, which I compelled myself to read, is that it’s racist, patronising, dialogue-heavy, galumphingly paced, and boring. The fiction editors were certain the piece was a shoo-in for the Pushcart Prize. Hmmm. Anyway, evidently there was pushback from their Editor in Chief, who raised questions, surprise surprise, about the representation of Tonto. Time passed. A sensitivity reader was engaged, but did not make it past the title (for real). The fiction editors held their ground. The EiC held hers and pulled the piece. Cue fracas. The fiction editors were eventually fired and they placed this piece about the danger of censorship to the literary world at Persuasion, Yascha Mounk’s obnoxious libertarian Substack. The piece has been lapped up by the anti-idpol crowd and given the ‘hmmm lots to think about here, sounds like things are going a bit far’ treatment by more centrist readers.

It is certainly true that there is a heightened awareness of and sensitivity to race and representation in literary journals and across the publishing sector in 2024 compared to 2014 and 2004. And this is a very good thing! We need more editorial conversations informed by anti-racist and decolonial thinking! Hesitation before publishing a piece you suspect is on the nose is a good thing. Yes, there are examples of over-reach as institutions and publications figure out what it is to take anti-racist work seriously – but this is not one of them! The story in question unambiguously and unironically relies on tired racist tropes and lacks literary merit. These are adequate grounds for an editor to pull a story. Is this censorship, as the fiction editors assert, or merely, as I would argue, the exercise of good editorial judgment? This is what editors do, they make decisions. If there is a hierarchy of editors at a magazine, rather than a horizontal organising structure, or a collective decision-making model, it is manifestly the role and responsibility of the person at the top of the hierarchy, to make a final call on what does and does not get published. Editors do not have a duty to anyone to publish their work; pulling a story from publication, especially a crap story, is not censorship, it is a legitimate exercise of editorial discretion. The fiction editors note that only somewhere between 1 and 2 per cent of fiction submissions to their periodical were published - were the other 98% censored? Hardly. I’ve gone on too long about this so I will leave it here in solidarity with all editors who take their time and deliberate over whether or not to publish bad work in the face of relentless accusations from the Persuasion crowd and their allies of being too woke, or intellectually un-free, or timid and conformist.

Thanks for reading Infra Dig! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.